Village Origins

Two local residents, Dr Jonathan Dicks and Mary Jane Lomer have written articles on the origin of the name Rowlands Castle. They are reproduced below with their permission and they retain the copyright.

Rowlands Castle – What’s in a name

by Dr Jonathan Dicks

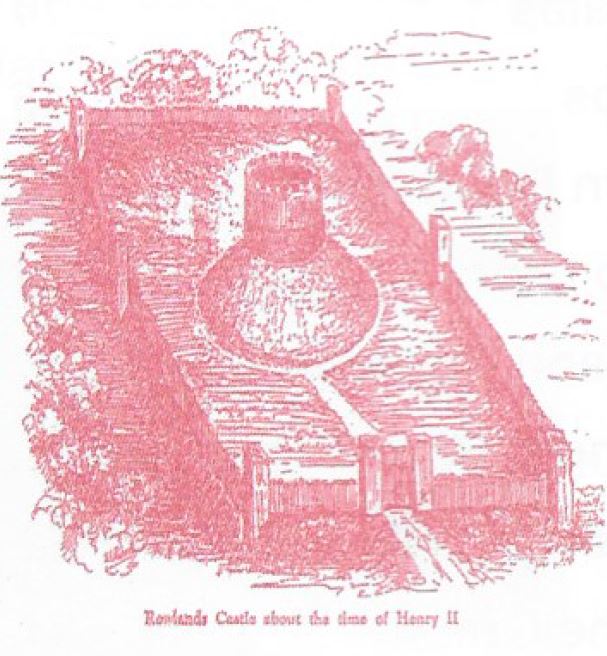

The castle has been, and probably always was, a significant feature from which the village of Rowlands Castle has acquired its name. The basic features of a ‘motte-and-bailey’ castle consisted of a wooden or stone keep (tower) situated on a raised earthwork called a motte. This was accompanied by an enclosed courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. The Normans first introduced this style of castle into England following the invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066. Rowland’s castle exhibits many of these features so it reasonable to assume that it was constructed after the Norman Conquest.

The conical motte is still clearly visible and is the only instance of a true Norman Mount in Hampshire (Williams-Freeman, 1915, 281). There would have been a tower on the motte creating the ultimate defensive position. This was enclosed by a ditch and rampart which was probably mounted with a wooden palisade creating the bailey. The bailey was a defended courtyard which would have contained the main hall and residence as well as other structures and workrooms built of timber, cob, wattle and daub with shingle and thatched roofs. Whilst the bank of the old bailey is still visible there has been no archaeological investigation of the interior to establish if there are any remains still existing below the present-day surface.

Figure 1.

Background:

Castles

After the Norman conquest of 1066 England was under occupation and the Saxon population resented and resisted the foreign intruders. The Normans consequently built many castles across England as symbols of their authority and supremacy. William the Conqueror ordered castles to be built along the south coast. These included Dover, the Tower of London, Arundel, Corfe Castle and Exeter. It would seem unlikely that Rowland’s Castle was built during this period as there are no early references to its construction. Significantly there was no reference to Rowland’s Castle in the Doomsday Book of 1086 whereas other local villages such as Charlton, Stoughton, Racton, Westbourne, Lordington and Hayling were cited (Morris, 1982). After William’s conquest, he gave Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, the Rape of Arundel, modern day West Sussex. Roger was one of William’s principle councillors and commanded the right flank of the Norman Army at Hastings. The Rape had been owned by the Saxon Godwins as well as much of East Hampshire. All their lands were confiscated by William and given to Roger de Montgomerie including the Manors of Warblington and Charlton which contained the area now known as Rowland’s Castle, but there were no references to any castle or village. There is still evidence of the bank and ditch that divided the manors of Warblington and Charlton running alongside the bridle way from the village to Whichers Gate (Route 42) indicating that Rowland’s was on the edge of the two manors.

After the death of William in 1087 he was succeeded by William Rufus (1087-1100) and then Henry I (1100-1135). Robert Belleme, the son of Roger de Montgomerie, had been part of an unsuccessful rebellion against Henry and in 1102 all his lands which included the Manors of Charlton, Warblington and Idsworth were confiscated by the King. During the revolt Robert Belleme had built a castle at Bridgnorth, Shropshire so it is unlikely that he would have also built another castle at Rowland’s but this is not impossible. It was during Henry I’s reign that a Norman castle was built inside the Roman fort at Portchester.

Upon Henry I death in 1135 his daughter Matilda and her cousin Stephen of Blois contested the throne of England in what is referred to as the civil war known as the Anarchy (1135-1154). The English barons, who had vowed to Henry I to support the accession of Matilda to the throne reneged and Stephen seized the throne. Some of the barons and noblemen then turned on Stephen and invited Matilda to come and be crowned in his stead. During the civil war the English barons took advantage of political unrest and the state of anarchy that prevailed to build their own castles which had until then required the authorisation of the king. The building of unlicensed castles during the Anarchy presented a major problem to the crown and in 1154 it has been estimated that there were some 274 active castles of which only 49 were in the hands of the king (Rowley, 1997, 75). It is highly probable that it was during this period that the castle at Rowland’s was built some 70 to 80 years after the Norman Conquest.

Henry II, Matilda’s son, inherited the kingdom on Stephen’s death in 1154 and in order to establish his authority he had many of the unauthorized castles that had been built during the Anarchy destroyed. Both Henry II and his youngest son John not only destroyed a number of unlicensed castles but significantly increased the number of royal castles. It is possible that the castle at Rowland’s, if it were unlicensed, suffered this fate of being destroyed which would suggest that the castle was relatively short lived.

Churches

Churches and church records are a major source of historical information but it would seem that the earliest church in Rowland’s Castle was St Johns built in the 1830’s followed by the Church on the Green built in the 1880’s. Many parishes with churches were listed in the Domesday Book of 1085AD of which a substantial number were of Saxon origin. There are the remnants of Saxon work in several local churches such as St Hubert’s at Idsworth but there are no records of any church at Rowland’s Castle in this time frame. The church at Idsworth was originally built in the ninth century to serve the local Saxon settlement which probably included any agricultural inhabitants living in the area now known as Rowland’s Castle. This would indicate that it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that Rowland’s warranted a church.

Maps

One of the earliest recorded evidence of the name Rowland’s Castle can be found on Isaac Taylor’s map of Hampshire dated 1751. This shows a cluster of buildings around the green, obviously before the railway which did not arrive until the mid-nineteenth century. The building now known as Deer Leap maybe represented by a square outlined south of the green. Rowland’s was spelt without an apostrophe. Figure 2. Isaac Taylor’s Map of 1751.

Forty years later, Milnes’s map of 1791 shows little has changed. Stansted House was now owned by Richard Barwell who developed the estate and Rowland’s Castle is depicted at the end of one of the avenues to the house. The major ‘road’ would seem to be a north-south track from Havant to Petersfield. Perhaps this is the impetus that encouraged the growth of the village. It is of interest to note that there was a site of a Brick Kiln as early as 1791, and that the Staunton Arms hostelry was then called the ‘Robin Hood Inn’. Figure 3.

Discussion

It has been suggested that the castle was named after one of William the Conqueror’s knights called Roloke and hence Rowland’s Castle. The list of knights that accompanied William taken from the plaque in the church at Dives-sur-Mer, Normandy, France, where William and his knights said mass before setting sail to invade England in 1066 does not seem to contain a knight called Roloke. Any castle built in England after the invasion needed the authorisation of the king who had given Roger de Montgomerie permission to build a castle at Arundel. It would seem unlikely that another castle would have been authorised to be built by Roloke on Roger de Montgomerie’s land.

In 1817 Rowland’s Castle was described as a small hamlet at the extremity of a beautiful avenue leading to Stansted House surrounded by woods (Bingley, 1817, 55). The Ordnance Survey map of 1810 would seem to support this description showing the avenue of trees leading directly to Rowland’s Castle. Figure 4.

Bingley goes on to describe that all that remained of the castle were a few foundation walls consisting of regular masonry 8 feet thick probably from the keep forming a quadrangle 20 feet square. There was a door in the west wall and the whole surrounded on the west, south and east sides by a double vallum. Interestingly Bingley goes on to state that ‘from the material used in the walls and the style of the building we must conclude them to be of Roman origin’ (Bingley, 1817, 57).

A hundred years later in 1914 a description of the castle was a ‘raised mound of the castle was 31 feet above its ditch and 40 feet in diameter at the top’, but now only one large piece of flint masonry five feet thick was visible. Significantly, however, it was now recognised as the remains of a Norman Castle (Williams-Freeman, 1915, 400-1).

So how did the village acquire the name of Rowland’s Castle? The evidence suggests that it was not until the mid-eighteenth century that there was any village at all but just a few buildings. It was practice for some places to be known by features within the landscape and in the eighteenth century the castle at Rowland’s was thought to have been of Roman origin hence Roman Castle. In 1817 it has been suggested that the name was changed to Rowland’s ‘as more congenial to the sentiments of the vulgar, who supposed it to have been the residence of a famous warrior, for such is the village tradition’ (Bingley, 1817, 55). It is also possible that by the mid-eighteenth century that it was recognised that the castle was not Roman but Norman. Either way Rowland’s, with or without an apostrophe, became the recognised name of the village. The arrival of the railway in the mid-nineteenth century saw the expansion and the development of the village as we know it today.

References

BINGLEY, W. 1817.

A Topographical Account of the Hundred of Bosmere, Havant, Havant Press.

ROWLEY, T. 1997.

Norman England, London, English Heritage.

MORRIS, J. 1982.

Domesday Book, Hampshire, Chichester, Phillimore.

WILLIAMS-FREEMAN, J. P. 1915.

Field Archaeology as illustrated by Hampshire, London, Macmillan and Co.

How did Rowlands Castle get its name

by Mary Jane Lomer

The origin of the name Rowlands Castle is a mystery. There are several myths surrounding the evolution of the name starting with rolokescastel from Saxon times meaning Red Clay found in the area. The ancient castle was supposed to have occupied the site at a Roman or Saxon Entrenchment. Romantic legends tell of a brave Giant Orlando Roland who “swam” across the Channel to rescue a maiden abducted from France who had been locked up shrieking in a castle turret! Another suggestion is that the area was frequented by many “forest free booters” knights and brave soldiers looking for hunting and a castle to live in. One Roland was credited with the building of a castle. There was also a “Knight or “Paladin” at the time of Charlemagne whose name was…Roland! He we killed while fighting in 778 and was featured as a hero in a ballad of the time called Le Chanson de Roland… An early pop star. Ties with France were strop in those days and what better way to honour a national war hero than to name castle after him!

This is an imaginative model of Rowlands Castle perhaps made by an apprentice of the Brickworks. It is now in the Bursleldon museum.

Stephen and Matilda were contesting heirs of Henry I and either of them could have been instrumental in fortifying the castle during the civil war between them.

Historians tell us that Henry II stayed there in 1177, he loved hunting and would not have wanted to destroy the castle. Suggestion is made that an earthquake helped the castle’s demise and that it fell into disrepair around 1400.

The embankment holding the railway line runs over the site of the castle and nothing remains of its walls and stone work which was obliterated by the building of the railway which cut through the “Dell” of the 1850s. The building of the principal Victorian residence “Deerleap” behind what is now Rowlands Home Hardware covered up any further remains of the castle. The flint wall bordering the property was built later, some think using flints from the castle. Behind Deerleap there is a flag pole on a grassy mound which marks the spot as an ancient monument, a Motte and Bailey castle, despite the impossibility of visiting it.