Idsworth: The Rise and Fall of the Clarke Jervoise Dynasty

Idsworth is the least known of the three local Estates. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, although the house is situated on a rise only 2 kilometres from Rowlands Castle off the road to Horndean, it lies at the end of a 300m drive and can only be seen from a distance. Furthermore, it has always been in private hands, so the public have never had access to it.

As is usually the case, the existing building is by no means the first Idsworth House. It is less usual however to find that its predecessors were built on an entirely different site. The existing building dates back no further than the middle of the nineteenth century: even so it is older than that at Stansted (like Uppark, rebuilt after a fire) while Staunton’s house was demolished altogether.

To locate the site of the earlier houses one has to look two or three kilometers north-east, across the shoulder of Idsworth Down. What is left of the previous house and garden can still be seen in the valley bottom, near the celebrated Saxon chapel in the area now widely known as ‘Old Idsworth’.

Background

There was a Saxon settlement on Church Down in the sixth and seventh centuries, recently excavated by Southampton University, but this was abandoned, and the inhabitants relocated to the current Chalton, Blendworth and Idsworth. There are signs of a village dating back to the ninth century in the region of Old Idsworth, but this had also disappeared by the end of the fourteenth century, possibly a victim of the plague.

By this time the area had passed through the hands of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, the most powerful man in England, who oversaw the building of St Peter and St Paul (later St Hubert), and of his son Harold, king until defeated at Hastings in 1066. William the Conqueror (or William the Bastard as he was less generously known) dispersed the conquered land among his followers. What is now Hampshire and Sussex were divided among Roger de Montgomery and Hugh de Port.

Idsworth is not mentioned in the Domesday Book and was probably at that time included in the manor of Chalton, which had been given to a brother of Baron Montgomery called Roger de Belesme. He was said to be ‘the personification of cruelty and rapacity who feared neither God, man nor devil’. As such, he was evidently considered just the man to be made Earl of Shrewsbury and may have been the origin of the local legend of Rowland the Giant.

Idsworth was probably separated from Chalton in 1102 when the Earl took the wrong side in a rebellion against William Rufus and fled the country, forfeiting his lands to the crown. It was subsequently granted to a succession of the kings’ supporters, with the name Idsworth first recorded, as Hiddeswrthe, in 1170 (Iddeswyrd was old English for ‘Iddi’s curtillege’ – curtillege being an area of land attached to a house). In the thirteenth century, it was granted by Queen Eleanor ‘in free alms’ to Tarrant Nunnery in Dorset.

With the abbess as overlord (which she remained until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539), Idsworth passed through several owners until arriving in the hands of the Banyster family in 1577. In 1613, the Banyster heiress married Robert Dormer, the third son of Robert, first Lord Dormer of Wyng and it was the Dormer family that built an extensive manor house close to the Saxon chapel to replace an earlier building.

The Banysters and Dormers were staunch Catholics throughout the 370 years when they owned Idsworth but their isolated position allowed them to keep out of harm’s way although there is evidence of a Civil War battle in the fields north of South Holt Farm. 340 musket balls were found in one field alone.

The Clarke Jervoise family

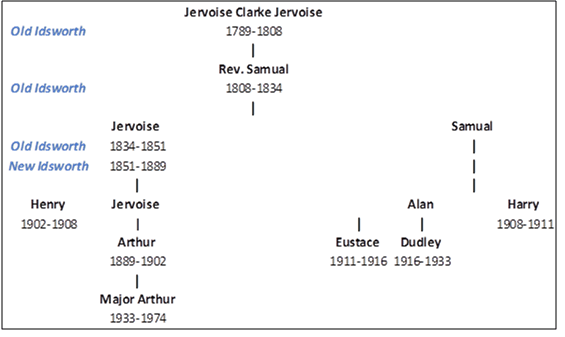

In 1789 Charles, the eighth Lord Dormer, sold ‘the manor of Idsworth and Holt Northmarden, Idsworth Park and estates in Idsworth, Chalton and Holt Northmarden, Stoughton and Compton’ to Jervoise Clarke (1733-1808?) of Bellmont in Bedhampton.

Jervoise (pronounced Jarvis) had already, in 1780, purchased the Manor of Chalton and Five Heads. Like many such families, the Clarkes feathered their nest by judicious marriages to wealthy heiresses. Jervoise’s father was Samuel Clarke whose wife was Elizabeth Jervoise. Her family had owned extensive property in Hampshire and Wiltshire since the sixteenth century, and several of its members had been elected to Parliament.

When Clarke inherited various other Jervoise properties, the terms required him to add the Jervoise to his surname. He therefore became, oddly if euphoniously, Jervoise Clarke Jervoise. Jervoise himself then added further to the family wealth by marrying Kitty, the only child of Robert Warner, inheriting estates in Staffordshire.

Clarke Jervoise was a leading light of local society, including the gentlemen’s social club at the Bat and Ball which provided the financial backing for the famous Hambledon Cricket Club. Under the pub landlord, Richard Nyren, Hambledon became the first pre-eminent cricket club in the country, regularly beating teams raised by the counties, MCC and England during its heyday from 1760 to 1790. Clarke Jervoise rose to the position of President, one of his duties being the provision of venison for the annual dinner. When he failed to do so one year he was fined, not a dozen bottles of claret, the usual penalty for misdemeanors, but a whole buck. The result was an extra meeting to ‘Eat Venison and Drink Bonham’s and Fitzherbert’s Claret’.

Jervoise was succeeded at Idsworth in 1808 by his third son, the Reverend Samuel Clarke Jervoise (1770-1852), (rector of Idsworth, Chalton, Blendworth and Catherington, who had been joint purchaser of the estate with his father. The following year, Thomas, the eldest son who, like his younger brother, had been declared ‘lunatic’, died and Samuel disputed the will, claiming lands around Blendworth, including the site of the present house. The suit was not settled until 1826, when Samuel gained possession of the land, although the case had forced him to sell much London property. In 1811 he also sold off land in Staffordshire enabling him to consolidate at Idsworth by purchasing South Holt and Northwood Farms. To enhance his property he built an avenue of 195 limes and 22 beeches, a few of which can still be seen climbing Idsworth Down from Old Idsworth. The avenue was, in fact, reinstating a previous version planted in 1735 which had since disappeared.

In 1813 a baronetcy was granted to ‘Samuel Clarke Jervoise of Hanover Square (Middlesex), Idsworth Park (Hants) and Woodford (Essex).’ With various addresses to choose from, the Clarke Jervoises sometimes ignored Idsworth. In 1817, for instance, they advertised ‘Idsworth Park and mansion’ to be let for three years. ‘This place (till very lately known as the residence of the Dormer family) is pleasantly situated and calculated for moderate establishment.’ Prospective tenants were offered 300 acres of grassland, one hundred within the Park and ‘exclusive privilege of sporting over a manor of about three thousand acres’.

The sales pitch may have claimed Idsworth to be ‘pleasantly situated’ but Samuel’s wife had complained regularly about the ‘dark, dank valley’ in which Idsworth lay, and in 1834 Samuel resigned his living and took residence thereafter in London, Brighton and Essex, leaving Idsworth to his son, another Jervoise Clarke Jervoise (1804-1889).

Jervoise’s diaries for 1834 to 1858 survive, allowing us some insight into his life. Much time, of course, was spent in London where the family always maintained a substantial home, first at 22 Bryanston Square (now the Swiss Embassy), later in Dover Street and Cadogan Square. Each year the Clarke Jervoises would spend up to four months a year in town on a long round of visits to the opera-house, concert hall and theatre, as well as attending balls. In the second half of May one year, his wife Georgiana saw four operas, two concerts and a play, as well as hearing Charles Dickens read from his latest work. Jervoise himself once saw the same opera twice in three days.

But the diaries also give a glimpse into Jervoise’s life at Idsworth. The early years are described as a mixture of hunting and shooting, dealing with the estate and the improvements he deemed necessary, sitting as a Magistrate and on the Board of Guardians, going to the races, and driving to see friends. The entry for November 1st, for example, notes: “Went in my father’s carriage to Horndean and found the Regulator (ie London) coach nearly full but got a place …. Saw some fine Dorset lambs near Guilford (sic). I got off at Kingston and took a chaise to The Oaks, lost our way, arrived in the dark, found Sir Charles and Elizabeth dined out, so drank tea with Georgiana, whose cough was not much better.”

Some days seem to have been as busy as period dramas would have us believe. Two weeks after the entry quoted above, we find Jervoise organising both the bricklayer and the carpenter, the latter “cutting down beds and removing the curtains which were full of dust and live flies. Cargo of goods arrived from Arundel. Barouche and servants arrived from London. Three women servants came from Yorkshire, so we were obliged to dismiss the scullery maid we had hired in this neighbourhood, gave her £1 for her trouble, her wages were £5 a year. Henry arrived with my horses from Chiswick. Lash, my new butler, brought a letter from my mother and an old book of mine, ‘300 Animals’, which was in great favour with me when I was a boy.” The number of letters passing, especially between Jervoise and his parents, is very notable.

Other days were less momentous but important nonetheless – “June 10: New Butter arrived” – yet others, less momentous than they should have been – “April 28: My Birthday, which everyone forgot but I.”

Like many aristocrats of the time, Jervoise had a wide range of interests. Beside those already mentioned, evidence is supplied for instance, by a photograph of a Roman pot ‘found at Rowlands’ Castle, Hants’ by ‘Sir J. Clarke Jervoise Bart’. Given the proximity of Fishbourne and Portchester, this is not surprising and his discovery may relate to the reported finding on his land of a well-preserved denarius from the period of the Emperor Domitian in the 1860s. One hundred years later several pots were found near the chapel.

Much later, in 1882, Jervoise, displaying a hitherto unrecorded interest in medicine, published a 63 page pamphlet entitled ‘Infection’. In this he boldly argued that there are no such things as germs, denied the possibility of infection and attacked the quarantine regulations as ineffective and unnecessary. The pamphlet included ‘remarks by Miss Nightingale’, the meaning of which remain disputed. It seems unlikely that Florence shared the author’s radical views.

The Atmospheric Railway and the new house

Meanwhile the industrial revolution was having consequences even in rural Hampshire. From 1843 to 1848 Samuel and Jervoise had been in negotiation with the Direct London and Portsmouth Railway Company which was intending a compulsory purchase of the land on the west side of the estate, immediately in front of the house. Samuel had evidently tried unsuccessfully to petition the House of Commons against the ‘Atmospheric Railway’ although he and his son seem to have made plans from an early stage to use the proceeds of any sale to build a new house.

At any event the family finally did very well from the deal, Jervoise noting in his diary on March 24 1848 that, in return for agreeing not to oppose the railway extension, he was to be paid £30,000, a sum worth many millions in today’s money. From this time onwards, Jervoise made most of his trips to London and to Brighton, where his parents now lived, by train, frequently travelling up to town and back in a day.

Plans were drawn up from 1847 for a house on a spot that offered vistas as was the Victorian style; on the one hand, up to the folly on Idsworth Down (of which little now remains and even less is apparently known), on the other across to Northwood Farm in Forestside. The first stone was laid by the Rev. Sir Samuel Clarke Jervoise with a silver trowel on 7 May 1849. An inscription in a bottle was placed under the foundation stone. The workmen were given a hogshead of ale to celebrate the occasion. Samuel was also invited to lay the first stone for the new church at Blendworth but had to decline, presumably due to old age or illness.

The architect was the ‘frank and plain-spoken’ Scot, William Burn (1789-1870). Averse to publicity, he was described enigmatically by Pevsner as ‘the most mysterious of Victorian architects’, but he was nevertheless one of the most prolific designers of country houses. He was responsible for sixty new buildings (sixteen of them in England), and is said to have had a hand in about 700 buildings altogether.

Burn has been given credit for laying down the template for the way in which early Victorian country houses were arranged, often with ‘business rooms’ and family wings, and with the offices divided into zones under the butler, the housekeeper and the cook. A key requirement was to enable the family to have as little tiresome contact with the servants as possible. Even so, it has been noted that ‘he nearly always made a point of providing the servants with decent accommodation’, a fact for which later residents are grateful. Idsworth itself was organized as a substantial manor house on three floors, with a clock tower (dated 1849), and a lower wing on the north side that accommodated the servants’ quarters, the estate offices and stables. There were two detached buildings, a walled kitchen garden and extensive other gardens.

Idsworth was the second of his three Hampshire houses, designed in the Scottish Baronial (or neo-Jacobean) style in red brick in Flemish bond with bath stone dressings. The by now rather dilapidated old Idsworth was demolished and much of the material used in the new. Burn visited quite regularly to check on progress, while Jervoise also met him occasionally at his London office. Work seems to have progressed smoothly, although in September Jervoise noted that work had stopped due to a shortage of white bricks and timber. More seriously, one workman died during the construction when stone for the landing was being swung from a rafter and fell. Burn himself fell on 10 July 1851, ‘but not heavily’.

Samuel had visited in December 1850, his son recording that he ‘does not like the Weathercock and Vane which has just been sent down according to Mr. Burn’s sketch.’ By September 1851 the Well House was being built and a pump installed and by October planting was being carried out to east and west of the house

On the estate, the alignment of the roads was changed to enlarge the park of the new house. The line of Treadwheel Road, which until then had turned north-east at Woodhouse and passed right beside Treadwheel Farm, was moved south and straightened, extending the park. The road north from Woodhouse, which had previously made a series of loops east of a straight line, was also straightened to achieve the same end, while what had previously been a public road, running north from the farm, became the private front drive.

Further afield, Jervoise changed the course of Links Lane to its present route rather than heading west through what is now the golf course. It is said that this was in sympathy with his horses which found the incline up Bowes Hill not to their liking. If the feelings of the horses were considered, there was, of course, no need to consult in any way with the local populace before making these changes.

Life in the new house

Jervoise and his wife and children moved in on 8 December 1851 with a household of seven male servants, four female, and two governesses. The Rev. Samuel named the house Wick Hanger, though this evidently did not stick. The following year he died and Jervoise became 2nd baronet. In 1857 he was elected a Member of Parliament for South Hampshire, a seat he held until defeated in 1868. His name appears three times on the large plan of MPs painted on the wall of the Great Court in Winchester. He was also a JP and a Deputy Lieutenant of the County.

Sadly, there is an unexplained gap in Jervoise’s diary between December 1851 and December 1852 and the entries thereafter become less easy to read and end altogether in 1858. Unfortunately, while Jervoise’s accounts of his hunting and shooting are considerably longer and more detailed than later readers require, he tells us little about more important events. There is no mention of any plans made for the house, how Burn came to be commissioned or what the costs were for example. Presumably the private family papers cover such issues.

Fortunately, Lady Georgiana also kept a diary, covering later years. For her, life at Idsworth was one long round of visits from friends and family. She noted on 29 June 1865 that ‘This is the first time for nearly six years that I have been alone.’ During the autumn and winter, hunting and shooting took place on an almost daily basis. The extensive ice house, still visible in the chalk quarry to the north-west, was of great importance. On one day in January 1866, for example, 140 pheasants, 51 hares and 23 rabbits were shot.

Even so, rural life was not enjoyed by all. Jervoise’s diary noted in March 1850 that ‘Georgiana tells me that it is quite necessary for Teresa (the eldest of their four daughters) that she should have a house in London and will continue so until the eldest is settled. Want of variety for the elder, want of means of educating all, the dull and dirty state of the countryside in winter for females generally, and even in this season the mischance of a long walk not providing a single human object, were all quoted in proof of the sacrifice made by the female part of the family living in the country.’

The suffering of the females however was probably of a lower order than that endured by the Clarke Jervoises’ second son, Henry, who was serving in the Crimea. A bundle of over 100 letters to his parents still survive.

In 1851 Jervoise had built a school at Idsworth (also designed by Burn) for the older village children, hitherto taught at Dean Lane End (it operated until 1950), but Georgiana did not have a very enlightened view of the working classes. Describing the Boxing Day meet of 1865, she noted that ‘all the rabble of the countryside out’. Even so, she did her share of ‘poor peopling’. She arranged for all the children at the school to have their hair cut twice a year, organised a school clothing club and a Christmas tea for women and children. Special occasions were marked. The Prince of Wales’ marriage in 1863 saw a dinner for labourers and their wives at Chalton and a bonfire on Windmill Down until 11pm. The marriage of one of Jervoise’s daughters in January 1867 was marked by a servants’ ball which carried on until ten minutes to eight the next morning. One result was that when Jervoise went to meet the Hambledon Hunt next day, he found his groom drunk and no horse available. In apocryphal Victorian style, he was not amused.

The school was just part of Jervoise’s building programme: he built houses in Chalton, Clanfield, Finchdean and in Pyle Lane, Horndean, many incorporating a prominent stone on the frontage with the letters JCJ which can still be spotted. At the top of the Links Lane, near the junction with Bowe Hill, he built a water tower, originally to supply Idsworth House and its estate, but later providing water for the whole village which, in those days, was in the parish of Idsworth. Seventy feet high, it held 25,000 gallons and was a local landmark until demolished as recently as 1964.

The long decline

Georgiana died in 1873, a year after her oldest son and was followed to the grave by her husband in 1889. He was succeeded as 3rd Baronet by his grandson Arthur (1856-1902) who, with other places of domicile to choose from, seems to have shown little interest in Idsworth. From 1890 the house was rented out, initially to the Speaker of the House of Commons. In 1892 repairs included work on the water and sewage systems and the replacement of the earth closets by WCs. From that year until 1908 the house was let to John Bradley Firth and it was he who laid down the cricket field and built the pavilion and the rackets court.

Arthur had died in 1902, without heir, and the estate passed first to his uncle Henry (1831-1908), Jervoise’s second son and, after his death in 1908 to Harry (1832-1911), Eustace (1871-1916) and Dudley (1876-1933), the heirs of Jervoise’s younger brother Samuel. During these years Idsworth was progressively modernised. Electricity was installed in 1908, albeit with batteries charged by an oil-powered engine. A motor mower was purchased and, next year, glasshouses were built on ‘all three sides of the north end of the kitchen garden’. Electric lights reached the house in 1910 and central heating a few years later.

Henry had also inherited his father’s enthusiasm for building, adding further houses in Chalton, Old Idsworth, Woodhouse, Finchdean, Forestside, Horndean (including the building that is now Keydale Nursery’s café) and in Wellsworth Lane. In most cases the letters HCJ can still be seen on their frontages. A few more were added in the years between 1934 and 1947 though these are clearly of an inferior quality.

In 1912, the twenty-five-year-old architect H.S. Goodhart-Rendel, the man responsible for the sympathetic restoration of Idsworth chapel at this time, was commissioned to alter the house. A new portico entrance was added to the frontage (a porte-cochere of the Doric order) with a tile-hung parapet and, on the north east corner a large, single story extension was built, used variously as a drawing or music room.

An article of 1920 refers to the beauty of the 5,000-acre estate whose ‘gardens and grounds near the mansion house are kept in a state of excellent cultivation.’ Orchids, peaches, and nectarines were evidently cultivated in the glasshouses. The house itself contained many antiques, including the Roman urn dug up on the estate and an outstanding Canaletto, a view of Venice from the Rialto Bridge. The painting was eventually sold on the London art market in 1997 for an undisclosed sum.

This was the highpoint of the Idsworth estate, as it was for so many others. The long agricultural depression that began in the 1870s gradually eroded the finances and the power of the landowning class. The breakup of the great estates had begun before the First World War and, by the ‘20s, more land had changed hands than at any time since the Dissolution of the monasteries.

During the Great War the house had been a convalescent home for Belgian soldiers with the family confined to separate apartments. After the war, austerity started to bite. In 1918, land amounting to 2,200 acres around Catherington, Clanfield and Horndean was sold, resulting in extensive building of bungalows and small houses in the Catherington/Horndean area. Three years later, the whole of old Idsworth was auctioned off by Sir Dudley Clarke Jervoise as a ‘Sporting and Agricultural Estate’. This consisted of a huge triangle of land and property from Finchdean and Dean Lane End in the south, east almost to West Marden and north to Woodcroft Farm, north-east of Chalton. Altogether it amounted to 1,851 acres.

In 1923, the kitchen garden, orchard, ice house and gardener’s cottage were leased in return for produce, and the house itself, and its shooting rights were leased to a Mrs Quentin Dick, who shortly became Lorna, Countess Howe. In 1925-6 a bungalow was built for her kennel man. The dogs evidently lived in what had been the Well House.

In 1933 Dudley, the 7th and last Baronet, died leaving no legitimate heirs. Four holders of the title had expired within fourteen years and the death duties that resulted were disastrous for the estate’s finances, forcing the series of disposals.

What was left of the estate now either passed to, or was purchased by (accounts vary), Major Arthur Clarke Jervoise (1882-1974), the illegitimate son of Arthur (the third baronet). Countess Howe continued as lessee until 1944 (her rent increasing from twelve hundred a year to seventeen hundred). In 1939 she had offered the house to the Admiralty as a hospital and the navy did not leave until 1946/7. It was planned for Courtfield School to relocate from Bognor, though this evidently never happened.

Eventually Major Arthur Clarke Jervoise himself moved in with his large collection of cars. But he was unable to prevent the financial side deteriorating further and in 1962 the Major was forced to mortgage the house and surrounding 273 acres to Newcombe Estates, which fully acquired some parts (including Wick Hanger) in 1970.

Life after the Clarke Jervoises

In December 1974, the Major died, ending the Clarke Jervoise occupation of Idsworth. He is commemorated in the church at Chalton and the family mausoleum can be found in the churchyard there.

In 1977 the property was advertised for sale, prospective buyers being offered ‘a fine Victorian mansion … ideal for institutional, educational and similar uses’. The prospectus boasted of five reception rooms, 28 bedrooms and nine bathrooms. In addition there were outbuildings, gardens, cricket ground and pavilion, bungalow, squash racquets court, walled kitchen garden with cottage and four further detached cottages, ‘extending in all to about 19 acres’.

Eventually the estate was divided up into nearly twenty properties and the Idsworth Park Residents Association, with most of the owners as members, was set up to manage the communal areas.

On the night of February 17/18, 1987, the house suffered major damage in a fire but, unlike Stansted and Uppark the building survived. The ornate gold-embossed dining room ceiling collapsed and carpets, antique furniture and oil paintings were ruined but Burn, the architect, had been well versed in the then relatively recent practice of using of wrought iron in construction and it may well be that the use of iron beams saved the building from collapse.

Conclusion

Idsworth Park today represents a shadow of its former glory, but it does at least still survive. Until the 1960s, such houses were being demolished at the rate of one every day. This disgraceful policy has now been discontinued and every effort is made to preserve our heritage. The buildings are now Grade II listed and many of the trees have preservation orders, including the specimen of Canadian Redwood, the world’s tallest tree, which Jervoise Clarke had imported in the early 1850s, one of the first such trees to arrive here. But the costs of keeping such properties in good order is immense. Without very substantial funds it is impossible to maintain the main house and features such as the walled garden at the sort of level attainable by the landowning aristocracy of the past.

While those areas converted to small individual homes can be managed reasonably easily, the future for large country houses like Idsworth must always be uncertain. In times past independent schools, offered a lifeline, as exemplified by Ditcham. Nowadays, the very best can be saved by the actions of the ‘new aristocracy’, those city financiers, media stars and large corporations that benefit from the status that ownership of a bit of history can bring, or of those whose ‘old money’ can at least provide a sufficient long-term income for the National Trust to be able to afford to own and maintain what had once been their family home. Others more often depend on their possible viability as a hotel or as the bargaining chip in plans to develop the grounds for housing.

About Guy Phelps, author

Guy Phelps has lived in what used to be the servants’ quarters of Idsworth House for sixteen years. He retired from a career in the media in 2003. With no background as a historian, he set out to find out what he could about his new home, using as a starting point a brief document compiled by a fellow resident.